Editor’s note: This article is so much indebted to William L. Craig’s “The Indispensability of Theological Meta-ethical Foundations for Morality” and to Norman L. Geisler’s “Any Absolutes? Absolutely!”

© 2010 by Jensen DG. Mañebog

LET US INVESTIGATE the moral foundations suggested by non-theists to see if they could satisfactorily explain some things we know about morality. Some of the ethical theories listed below (like Utilitarianism, Deontological Theory, etc.) are not necessarily athesitic in nature but they are nonetheless included here because some atheists use them to evade anchoring morality on God.

The reasonably supposed objective feature of morality (tackled in the previous articles) gives us the guideline that any suggested ethical system which either admits relativism or falls short of justifiably establishing absolute or objective morality must be considered as inept, if not downright flawed.

1. Convention, human experience, human need & human reason

A) Convention

Some secularists maintain that the basis for morality is conventional. They hold that the rules of morality were just fabricated by human beings over many generations. They point to rules such as abstaining from injury, lying, theft, assault, killing, and so on and so forth, which they claim to be not really coming from God. “Nobody thinks that if God had not told us this, if God had not delivered these rules to Moses, then we would not see anything wrong with one's stealing, assaulting, and killing.”

Therefore, the theory claims that people know the difference between right and wrong because they had derived this from experience and convention. The role of religion and ethics, according to secularists, has been to reinforce this ‘conventional’ morality.

B) Human experience

Some secularists explain that moral rules were derived from human experience. “You do not have to be religious to realize that for human beings to live in peace and happiness, they must not assault each other.”

Through experience, they explain, one may want to assault, but he does not want to be assaulted. If he is tempted to steal, still he does not want to be stolen from. And although he is tempted to kill, yet he does not want to be murdered. From this recognition, the rule allegedly thus emerged: “Let no one do these things. Then we can live in peace. Then we can realize the human good we need.” Secularists aver that there is every reason why human beings should have evolved these rules without having to be told by God that these are valid.

C) Human need & human reason

Secularists distinguished between nature and convention. Some of them hold that some things are by nature and that some things are by convention. Ethics is said to be by convention, but it has a natural basis—not natural law, not some law written in man's heart, not some law written in Scriptures. The natural basis of ethics, they assert, is human need and human reason.

To prove this proposition, they point to the certain things which all of us hate: we hate to bleed, we hate to be wounded, we hate to be killed, and we hate to be stolen from. And it is contended that we intelligently make our laws according to this.

Thus, it is concluded that the natural basis is certain universal needs: the need for security, for safety, for love, and the need to bring up the families in security and to teach our children to fulfill our own potentials as we can. “Having these needs, we got reasonable rules and they are important.” Hence, the Godless ethics: “We don’t need rules from God—all we need is to be human, to be a human being, to have the needs we have, and to have some human intelligence or reason.”

Analysis:

Indeed, in the secularists’ view, “objective right and wrong” does not exist at all. As they themselves submit, morality is just “conventional.”

However, if secularism is true, then it becomes impossible to condemn war, oppression, or crime as morally wrong. Some actions, say, incest, may not really be biologically or socially advantageous, and so in the course of human evolution it has become taboo. But on secularist position, there is nothing really wrong about it or about raping someone.

If, naturalists say, moral rules are “nothing but the customs…that this or that culture adopts over the course of time” as Richard Taylor indeed said(Ethics, Faith, and Reason,” Englewood Cliffs, N. J.: Prentice Hall, 1985, p. 57), then the nonconformist who chooses to flout the herd morality is doing nothing more morally wrong than being merely ‘uncultured.’ Nor, by the same token, can one praise brotherhood, equality, or love as good. In secularist standpoint, it really does not matter what values you choose, for there is no right and wrong—moral good and evil do not exist.

There is no more difference between moral right and wrong on the secularist perspective than driving on the right-hand side of the road versus the left-hand side of the road. It is simply a societal convention. And the modern evolutionist thinks these conventions are just based on socio-biological evolution. According to Michael Ruse, a professor of the philosophy of science:

“The position of the modern evolutionist ... is that humans have an awareness of morality ... because such an awareness is of biological worth. Morality is a biological adaptation, no less than are hands and feet and teeth. ... Considered as a rationally justifiable set of claims about an objective something, [ethics] is illusory. I appreciate that when somebody says, ‘Love thy neighbor as thyself,’ they think they are referring above and beyond themselves…. Nevertheless … such reference is truly without foundation. Morality is just an aid to survival and reproduction and … any deeper meaning is illusory.” (Michael Ruse, “Evolutionary Theory and Christian Ethics: In The Darwinian Paradigm,” London: Routledge, 1989, pp. 262, 268–69, emp. added).

There really isn’t any objective morality in Secularism. We suppose that every one of us would agree that it is wrong to kill babies and that the holocaust was morally wrong. But according to the famed secularist Richard Taylor, “The infanticide practiced by the Greeks of antiquity did not violate their customs. If we say it was nevertheless wrong, we are only saying that it is forbidden by our ethical and legal rules. And the abominations practiced by the Nazis … are forbidden by our rules, and not, obviously, by theirs.” (Richard Taylor, “Ethics, Faith, and Reason,” Englewood Cliffs, N. J. :Prentice-Hall, 1985, p. 1)

“Objective morality” means that moral rules are non-conventional. They are not simply based on human apprehension, but these are values that hold regardless of whether anybody believes in them or not. If the Nazis had conquered the world in the Second World War and had eliminated everybody who disagreed with their anti-Semitism, we maintain that anti-Semitism would still be wrong. It would still be immoral whether or not everyone agreed to it. This is an example of an objective wrong!

In secularist view, however, there are no such things as moral obligations or objective right and wrong. Suppose one person kills another one and takes his goods, the non-theist Taylor says:

“Such actions, though injurious to their victims, are no more ... unjust or immoral than they would be if done by one animal to another. A hawk that seizes a fish from the sea kills it, but does not murder it; and another hawk that seizes the fish from the talons of the first takes it, but does not steal it, for none of these things is forbidden. And exactly the same considerations apply to the people we are imagining.”(Richard Taylor, “Ethics, Faith, and Reason,” Englewood Cliffs, N. J.:Prentice-Hall, 1985, p. 14)

Therefore, as Dostoyevsky said, all things are permitted once you get rid of God.

Regarding human nature, human need & human reason as suggested ‘foundations’ of morality, we may ask, “If there is no God, then what’s so special about human beings?” In the absence of God, there is no reason to think that human beings have these non-natural properties.

On the atheistic view, some actions, say, rape, may not be advantageous in the society and so, in the course of human development, had become forbidden. But that does absolutely nothing to prove that rape is really morally wrong. On this viewpoint, if you can escape the social consequences, there is nothing really wrong with you raping someone. And, thus, without a sort of a Supernatural being, it is hard to have absolute right and wrong that imposes itself on our conscience.

We do not in any way discredit the role of human intelligence and reason in ethics. In fact, we acknowledge that reason is necessary in determining which course of actions is morally preferable, in making moral decisions, and in performing moral actions. Indeed, moral judgments must be supported by good reasons, and morality is an effort to guide one’s conduct by reasons—that is, to do what there are the best reasons for doing. Nevertheless, to suppose that human reason is never God-given and that it exists with no non-natural property whatsoever would give us no reason to trust our own reason or thinking. As C. S. Lewis puts it:

“Supposing there was no intelligence behind the universe, no creative mind. In that case nobody designed my brain for the purpose of thinking. It is merely that the atoms inside my skull happen for physical or chemical reasons to arrange themselves in a certain way, this gives me, as a bye-product, the sensation I call thought. But if so, how can I trust my own thinking to be true? It is like upsetting a milk-jug and hoping that the way the splash arranges itself will give you a map of London. But if I can't trust my own thinking, of course I can't trust the arguments leading to atheism, and therefore have no reason to be an atheist or anything else. Unless I believe in God, I can't believe in thought: so I can never use thought to disbelieve in God.” (The Case for Christianity (1943), p.32, emp. added)

We learned in science that Naturalists are typically materialists or physicalists who regard man as a purely animal organism. But if man has no immaterial aspect to his being, then he is not qualitatively different from other animal species. On a materialistic anthropology, there is no reason to think that human beings are objectively more valuable than rats.

Clearly then, these suggested moral ‘foundations’ by secularists (convention, human experience, human need, human reason) are not capable of providing solid and sound foundation for morality, nor can they satisfactorily explain the “objectivity of morality” which we have ascertained in the previous articles.

2. Utilitarianism

In the attempt to explain what is right, Utilitarians define moral as what brings the greatest good to the greatest number of people in the long run. “A utilitarian will argue that we have to maximize the good for the greatest number…This theory, obviously, democratizes the distribution of the good” (Acuña, Andresito E., Philosophical Analysis (4th edition), pp. 295). Also having “no claim that one’s (personal) good should be given priority…This view obviously has tremendous popular appeal to the masses and tends to down-grade the snobbishness of the elite and the intellectuals” (Ibid. pp. 295, 303). No wonder, Utilitarianism became “the most influential moral philosophy in the last two centuries” (Ibid. p. 302).

Under this ethical theory, some proponents define the meaning of good quantitatively—that is, the greatest amount of pleasure. Jeremy Bentham (1748-1832) fits into this category. Other advocates, such as John Stuart Mill (1806-1873), view it qualitatively—that is, the greatest kind of pleasure for the greatest number.

Analysis:

As we’ve seen, one problem with the utilitarian view relates to deciding how “good” should be understood—quantitatively or qualitatively. Moreover, upon analysis, one would realize that utilitarian definition boils down to making right and wrong simply a matter of preference. Thus, it disguises this relativism in that it is the preferences of society that determines right, not preferences of the individual. Nonetheless, we could notice that this does not make morality any less of a convention than if right is defined by what benefits a single individual.

Norman Geisler points out some of the further flaws with this view. First, “no one can accurately predict what will happen in the long run. Hence, for all practical purposes, a utilitarian definition of good is useless” (Norman L. Geisler, "Any Absolutes? Absolutely!", a Christian Research Journal [internet download]). This is to say that we must still fall back on something else to determine what is good now in a short-term basis.

Second, it just “begs the question to say that moral right is what brings the greatest good” [Ibid.] (which is actually the reason this theory is appealing at initial glance). In this theory, one would still ask, “What is ‘good’”? Right and good “must be defined according to some standard beyond the utilitarian process” (Ibid.), else, they are merely defined in terms of each other, which is circular reasoning. So, utilitarianism must presuppose some higher law, the very same higher law that it tries to do without. It just brings us to another question that has not been answered: On what basis could the utilitarian view say that it is good for the greatest number of people to be happy?

The popular utilitarian John Stuart Mill responded and argued that the “greatest good” is defined as the “greatest happiness,” and that this is self-evident and, therefore, does not presuppose a higher law:

“According to the Greatest Happiness Principle,…the ultimate end, with reference to and for the sake of which all other things are desirable—whether we are considering our own good or that of other people—is an existence exempt as far as possible from pain, and as possible in enjoyments, both in point of quantity and quality…” (Boyce, W.D., Moral Reasoning [London: Univ. of Nebraska Press, 1978] p. 36.)

As Philosophy Professor Andresito Acuña interprets it, “John Stewart Mill… laid the information of his moral philosophy by stating categorically that there is an ultimate good—a summun bonum. All moral actions should be aimed at attaining this good. And Mill insists that this good is happiness.” [Acuña, Andresito E., Philosophical Analysis (4th edition), p. 303]

However, some flaws could again be noticed in this kind of explanation. It is not at all self-evident that “good” is equivalent to “greatest happiness.” Happiness is an expression of goodness, but it is not self-evident that happiness is the foundation of good. When we say that happiness is self-evidently good, we mean the same thing as saying that intelligence obviously is good. But that does not make intelligence the nature, or foundation, of goodness. Obviously, it also does not necessarily make actions that promote intelligence right just because they promote intelligence.

Happiness does not establish a sufficient foundation for absolute non-subjective morality. For one thing, it seems that absolute morality must be grounded in something greater than humans in order to be binding, because otherwise, it is purely subjective. For another, what if a violent rape would bring the greatest good (i.e., happiness) to the greatest number? Would that make the rape right? We suppose that even utilitarian would agree that it wouldn’t. Furthermore, what if billions of people delighted in the act of rape itself—if rape in itself made the majority of mankind happy? Would their happiness (the alleged “foundation of good”) itself be good? On the contrary, we would consider them seriously evil. It appears clearly that our subjective feeling of happiness itself needs to be judged by a standard that is above utilitarianism. Thus, happiness is an impossible foundation for real morality.

Utilitarianism cannot affirm absolute morality and cannot remain consistent. It must secretly be presupposing some standard outside of its own view when it affirms absolute morality.

3. Deontological Theory

Deontological theory in Ethics (especially pure deontology) assumes a moral law and says a moral act is what is done out of reverence for the law.

As Professor Acuña puts it, “the basic posit of the deontologist is, an act is morally right, on the basis of the nature of the act alone. The consequences of the act are unimportant in the determination of our moral obligation… The nature of the act can be judged on the basis of its conformity to an immutable moral rule. If the act is an instantiation (or example) of the moral rule, the act is right. If not, the act is wrong. The consequences of the act are unimportant. This version is called pure deontology” (Acuña, Andresito E., Philosophical Analysis [4th edition], pp. 310-311).

Analysis:

The deontological can be discerned to fall to inconsistency as well. We may ask the deontologists, “What makes the

immutable law moral?” To answer “thinking carefully about the moral law will cause it to appear to you” does not answer the necessary question: Where did this law come from in the first place? An ethical system should be able to establish why the moral law is moral and why it is absolute. The deontological cannot do this because it assumes the very thing we want to establish. It cannot answer this question: Why is “good” good?

A response would be that something which is desirable for its own sake is good. But again, we ask, “On what basis can we ground the assertion that “good is what is desirable for its own sake”? And don't we often desire for its own sake things that are clearly evil?

It looks that we would have to supply some other standard in order to determine of what we desire is good to desire. And if the standard is “what most people in society would desire,” then we have then reduced ourselves to determining morality by vote, by majority, by popular choice. (This will be discussed further in a later section).

4. Culture: Morals are mores

Another ethical theory suggests that what is morally right is determined by the culture to which one belongs. Ethics is defined in terms of what is ethnically acceptable. What the community says constitutes what is morally right for its members. Cultural practices are thus viewed as ethical commands.

It is held that whatever similarity may exist between moral codes in different social groups is simply due to common needs and aspirations, not to any universal moral prescriptions. (This is very much related to the earlier section about “Human need”. Hence, our discussion here may not be that very different from what we have commented in that section).

Analysis:

Aside from the fact that it admits relativism and thus fails to account for the objectivity in morality, the problem with this position is what is called the "is-ought" fallacy. As we know, simply because someone is doing something does not mean that one ought to do so. Otherwise, racism, rape, cruelty, and murder would automatically be morally right.

Furthermore, if each individual community's mores are right, then there is no way to adjudicate conflicts between different communities. For unless there are moral principles above all communities, there is no moral way to solve conflicts between them. Finally, if morals are relative to each social group, then even opposite ethical imperatives can be viewed as right. But contradictory imperatives cannot both be true. Everything cannot be right, certainly not opposites.

5. Right is Moderation

The famous Greek philosopher Aristotle believed that morality is found in moderation. The right course of action is the “golden mean” or moderate course of action between two extremes. Temperance, for example, is the mean between indulgence and insensibility. Pride is the moderate course between vanity and humility.

Courage is the ideal between fear and aggression.

Admittedly, moderation is often the wisest course. Take note that even the Bible says: “Let your moderation be known unto all men.” (Phil. 4:5, King James Version). However, the question is not whether moderation is often the proper expression of morality, but whether or not it is the proper definition (or essence) of morality.

Analysis:

Several reasons suggest strongly that moderation is not the essence of what is good. First, in many occasions, the right thing is the extreme thing to do. Emergencies, actions taken in self-defense, and wars against aggression are cases in point. In these situations, moderate actions are not always the best ones. Likewise, some virtues obviously should not be expressed in moderation. One should not love only moderately. Neither should one be moderately grateful, truthful, or generous.

Besides, there is no universal agreement on what is moderate. Aristotle, for example, considered humility a vice (an extreme), but Christians believe it is a virtue. Moderation therefore is at best only a general guide for action, not a universal ethical rule, much less the foundation of morality.

6. Right is what brings pleasure

Although Epicurus himself was more moderate, some Epicureans (4th century B.C. and following) were Hedonists who claimed that what brings pleasure is morally right, and what brings pain is morally wrong. As put forward by Aristippus of Cyrene (435-356 BC), “the attainment of maximum pleasure” is the “mainspring of human action in pursuit of the good life” (Vesey G. and Foulkes, P., Unwin Hyman Dictionary of Philosophy, Great Britain: HarperCollins Publishers, 1999, pp.131-132).

Being “the base of utilitarian ethics” (Ibid. p.132), proponents of this theory unsurprisingly claim, as utilitarians essentially do, that the good is what brings the most pleasure and least pain to the greatest number of people.

Analysis:

Since few things are all pleasure or all pain, the formula for determining what is good is more complicated in this theory. Another difficulty with this theory is that not all pleasures are good (e.g., sadism), and not all pain is bad (e.g., warning pains). Also, this theory does not specify what kind of pleasure should be used as the basis of the test. We know that there are physical, psychological, spiritual, and other kinds of pleasure.

Furthermore, a believer in an afterlife for instance would ask, “Are we to use immediate pleasure (in this life) or ultimate pleasure (in the next life) as the test?” We may ask also: Should our gauge be pleasure for the individual, the group, or the race? In short, this theory raises more questions than it provides answers.

7. Right is what is desirable for its own sake

Some ethicists define good as that which is desirable for its own sake, in and of itself. Moral value is viewed as an end, not a means. It is never to be desired for the sake of anything else, so they say. For example, no one should desire virtue as a means of getting something else (such as riches or honor). Virtue accordingly should be desired for its own sake.

Analysis:

Professor Geisler comments: “This view has obvious merits. Nevertheless, this definition seems to bring about several problems. First, it does not really define the content of a morally good act but simply designates the direction one finds good (namely, in ends).

Moreover, it is easy to confuse what is desired and what is desirable (i.e., what ought to be desired). This leads to another criticism. Good cannot simply be that which is desired (as opposed to what is really desirable), since we, as pointed out earlier, often desire what is evil. Finally, what appears to be good in itself is not always really good. Suicide seems to be good to someone in distress but really is not good, for it does not solve the problem; it is the final copout from solving the problem instead.”

8. Right is indefinable

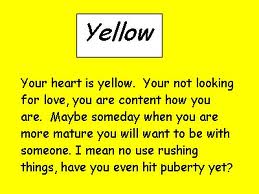

Some thinkers simply insist that good is indefinable. G. E. Moore (1873-1958), for instance, argued that every attempt to define “good” commits the “naturalistic fallacy”.

(This fallacy results from assuming that because pleasure can be attributed to good, then, they are identical.) Moore contended that all we can say is that “good is good” and nothing more. Just like the term yellow, the term good, for Moore, cannot be further defined. Attempting to define ‘good’ in terms of something else allegedly makes that something the intrinsic good.

Analysis:

There is some merit in this view. There can be only one ultimate good indeed, and everything else must be subordinated to it.

However, the view as such is inadequate. First, it provides no content for what good means. But if there is no content to what is right or wrong, then there is no way to distinguish a good act from an evil one. Further, just because the good cannot be defined in terms of something more ultimate does not mean it cannot be defined at all. A morally good God for instance could create morally good creatures like Himself. In such a case, even though God is the ultimate moral good, nonetheless, His goodness could be understood from the moral creatures He has willed to be like Himself.

Conclusion

We have seen therefore that the suggested ‘foundations’ of morality that are not rooted in a Supernatural Being or God are entirely subjective and/or non-binding. Proposing to use them as the basis of morality would result to having a world where there could no longer be actions that are really right or wrong.

We have seen that some of these non-theistic ethical systems are even inconsistent, and therefore could not be a ‘wise’ basis of morality—for they assume an objective morality that they have no right to accept, neither are they capable to provide on their worldview.

Guide Questions:

(Write your answer in the comment section below [add a comment]. Don't forget to click also the 'LIKE' button before writing anything.)

1. What are the unsound consequences if we would accept that moral rules are nothing but conventions we derived from experiences and needs?

2. Compare and contrast Deontological Theory and Utilitarianism. What are their strengths and weaknesses as ethical theories?

3. What’s wrong in reducing morality to what is moderate?

Related articles:

How to cite this article:

“Non-theists’ moral foundations: An analysis” @ www. OurHappySchool.com

NOTE: Click first the 'LIKE' button before writing any comment/answer in the comment section below [add a comment]. Thank you!

PROMOTE your products, services, student organizations, videos, etc. in OurHappySchool! Have an OHS AD PAGE for a price that even students can afford!

LET US INVESTIGATE the moral foundations suggested by non-theists to see if they could satisfactorily explain some things we know about morality. Some of the ethical theories listed below (like Utilitarianism, Deontological Theory, etc.) are not necessarily athesitic in nature but they are nonetheless included here because some atheists use them to evade anchoring morality on God.

LET US INVESTIGATE the moral foundations suggested by non-theists to see if they could satisfactorily explain some things we know about morality. Some of the ethical theories listed below (like Utilitarianism, Deontological Theory, etc.) are not necessarily athesitic in nature but they are nonetheless included here because some atheists use them to evade anchoring morality on God.

Courage is the ideal between fear and aggression.

Courage is the ideal between fear and aggression. Some thinkers simply insist that good is indefinable. G. E. Moore (1873-1958), for instance, argued that every attempt to define “good” commits the “naturalistic fallacy”.

Some thinkers simply insist that good is indefinable. G. E. Moore (1873-1958), for instance, argued that every attempt to define “good” commits the “naturalistic fallacy”.